[Epistemic status: fiction]

Thanks for letting me put my story on your blog. Mainstream media is crap and no one would have believed me anyway.

This starts in September 2017. I was working for a small online ad startup. You know the ads on Facebook and Twitter? We tell companies how to get them the most clicks. This startup – I won’t tell you the name – was going to add deep learning, because investors will throw money at anything that uses the words “deep learning”. We train a network to predict how many upvotes something will get on Reddit. Then we ask it how many likes different ads would get. Then we use whatever ad would get the most likes. This guy (who is not me) explains it better. Why Reddit? Because the upvotes and downvotes are simpler than all the different Facebook reacts, plus the subreddits allow demographic targeting, plus there’s an archive of 1.7 billion Reddit comments you can download for training data. We trained a network to predict upvotes of Reddit posts based on their titles.

Any predictive network doubles as a generative network. If you teach a neural net to recognize dogs, you can run it in reverse to get dog pictures. If you train a network to predict Reddit upvotes, you can run it in reverse to generate titles it predicts will be highly upvoted. We tried this and it was pretty funny. I don’t remember the exact wording, but for /r/politics it was something like “Donald Trump is no longer the president. All transgender people are the president.” For r/technology it was about Elon Musk saving Net Neutrality. You can also generate titles that will get maximum downvotes, but this is boring: it will just say things that sound like spam about penis pills.

Reddit has a feature where you can sort posts by controversial. You can see the algorithm here, but tl;dr it multiplies magnitude of total votes (upvotes + downvotes) by balance (upvote:downvote ratio or vice versa, whichever is smaller) to highlight posts that provoke disagreement. Controversy sells, so we trained our network to predict this too. The project went to this new-ish Indian woman with a long name who went by Shiri, and she couldn’t get it to work, so our boss Brad sent me to help. Shiri had tested the network on the big 1.7 billion comment archive, and it had produced controversial-sounding hypothethical scenarios about US politics. So far so good.

The Japanese tested their bioweapons on Chinese prisoners. The Tuskegee Institute tested syphilis on African-Americans. We were either nicer or dumber than they were, because we tested Shiri’s Scissor on ourselves. We had a private internal subreddit where we discussed company business, because Brad wanted all of us to get familiar with the platform. Shiri’s problem was that she’d been testing the controversy-network on our subreddit, and it would just spit out vacuously true or vacuously false statements. No controversy, no room for disagreement. The statement we were looking at that day was about a design choice in our code. I won’t tell you the specifics, but imagine you took every bad and wrong decision decision in the world, hard-coded them in the ugliest possible way, and then handed it to the end user with a big middle finger. Shiri’s Scissor spit out, as maximally controversial, the statement that we should design our product that way. We’d spent ten minutes arguing about exactly where the bug was, when Shiri said something about how she didn’t understand why the program was generating obviously true statements.

Shiri’s English wasn’t great, so I thought this was a communication problem. I corrected her. The program was spitting out obviously false statements. She stuck to her guns. I still thought she was confused. I walked her through the meanings of the English words “true” and “false”. She looked offended. I tried to confirm. She thought this abysmal programming decision, this plan of combining every bad design technique together and making it impossible to ever fix, was the right way to build our codebase? She said it was. Worse, she was confused I didn’t think so. She thought this was more or less what we were already doing; it wasn’t. She thought that moving away from this would take a total rewrite and make the code much worse.

At this point I was doubting my sanity, so we went next door to Blake and David, who were senior coders in our company and usually voices of reason. They were talking about their own problem, but I interrupted them and gave them the Scissor statement. Blake gave the reasonable response – why are you bothering me with this stupid wrong garbage? But David had the same confusion Shiri did and started arguing that the idea made total sense. The four of us started fighting. I still was sure Shiri and David just misunderstood the question, even though David was a native English-speaker and the question was crystal-clear. Meanwhile David was feeling more and more condescended to, kept protesting he wasn’t misunderstanding anything, that Blake and I were just crappy programmers who couldn’t make the most basic architecture decisions. He kept insisting the same thing Shiri had, that the Scissor statement had already been the plan and any attempt to go in a different direction would screw everything up. It got so bad that we decided to go to Brad for clarification.

Brad was our founder. Don’t trust the newspapers – not every tech entrepreneur is a greedy antisocial philistine. But everyone in advertising is. Brad definitely was. He was an abrasive amoral son of a bitch. But he was good at charming investors, and he could code, which is more than some bosses. He looked pissed to have the whole coding team come into his office unannounced, but he heard us out.

David tried to explain the issue, but he misrepresented almost every part of it. I couldn’t believe he was lying just to look better to Brad. I cut him off. He told me not to interrupt him. Blake said if he wasn’t lying we wouldn’t have to interrupt to correct him, it degenerated from there. Somehow in the middle of all of this, Brad figured out what we were talking about and he cut us all off. “That’s the stupidest thing I ever heard.” He confirmed it wasn’t the original plan, it was contrary to the original plan, and it was contrary to every rule of good programming and good business. David and Shiri, who were bad losers, accused Blake and me of “poisoning” Brad. David said that of course Brad would side with us. Brad had liked us better from the beginning. We’d racked up cushy project after cushy project while he and Shiri had gotten the dregs. Brad told him he was a moron and should get back to work. He didn’t.

This part of the story ends at 8 PM with Brad firing David and Shiri for a combination of gross incompetence, gross insubordination, and being terrible human beings. With him giving a long speech on how he’d taken a chance on hiring David and Shiri, even though he knew from the beginning that they were unqualified charity cases, and at every turn they’d repaid his kindness with laziness and sabotage. With him calling them a drain on the company and implied they might be working for our competitors. With them calling him an abusive boss, saying the whole company was a scam to trick vulnerable employees into working themselves ragged for Brad’s personal enrichment, and with them accusing us two – me and Blake – of being in on it with Brad.

That was 8 PM. We’d been standing in Brad’s office fighting for five hours. At 8:01, after David and Shiri had stormed out, we all looked at each other and thought – holy shit, the controversial filter works.

I want to repeat that. At no time in our five hours of arguing did this occur to us. We were too focused on the issue at hand, the Scissor statement itself. We didn’t have the perspective to step back and think about how all this controversy came from a statement designed to be maximally controversial. But at 8:01, when the argument was over and we had won, we stepped back and thought – holy shit.

We were too tired to think much about it that evening, but the next day we – Brad and the two remaining members of the coding team – had a meeting. We talked about what we had. Blake gave it its name: Shiri’s Scissor. In some dead language, scissor shares a root with schism. A scissor is a schism-er, a schism-creator. And that was what we had. We were going to pivot from online advertising to superweapons. We would call the Pentagon. Tell them we had a program that could make people hate each other. Was this ethical? We were in online ads; we would sell our grandmothers to Somali slavers if we thought it would get us clicks. That horse had left the barn a long time ago.

It’s hard to just call up the Pentagon and tell them you have a superweapon. Even in Silicon Valley, they don’t believe you right away. But Brad called in favors from his friends, and about a week after David and Shiri got fired, we had a colonel from DARPA standing in the meeting room, asking what the hell we thought was so important.

Now we had a problem. We couldn’t show the Colonel the Scissor statement that had gotten Dave and Shiri fired. He wasn’t in our company; he wasn’t even in ad tech; it would seem boring to him. We didn’t want to generate a new Scissor statement for the Pentagon. Even Brad could figure out that having the US military descend into civil war would be bad for clicks. Finally we settled on a plan. We explained the concept of Reddit to the Colonel. And then we asked him which community he wanted us to tear apart as a demonstration.

He thought for a second, then said “Mozambique”.

We had underestimated the culture gap here. When we asked the Colonel to choose a community to be a Scissor victim, we were expecting “tabletop wargamers” or “My Little Pony fans”. But this was not how colonels at DARPA thought about the world. He said “Mozambique”. I started explaining to him that this wasn’t really how Reddit worked, it needed to be a group with its own subreddit. Brad interrupted me, said that Mozambique had a subreddit.

I could see the wheels turning in Brad’s eyes. One wheel was saying “this guy is already skeptical, if we look weak in front of him he’ll just write us off completely”. The other wheel was calculating how many clicks Mozambique produced. Mene mene tekel upharsin. “Yeah,” he said. “Their subreddit is fine. We can do Mozambique.”

The Colonel gave us his business card and left. Blake and I were stuck running Shiri’s Scissor on the Mozambique subreddit. I know, ethics, but like I said, online ads business, horse, barn door. The only decency we allowed ourselves was to choose the network’s tenth pick – we didn’t need to destroy everything, just give a demonstration. We got a statement accusing the Prime Minister of disrespecting Islam in a certain way – again, I won’t be specific. In the absence of any better method, we PMed the admins of the Mozambique subreddit asking them what they thought. I don’t remember what we said, something about being an American political science student learning about Mozambique culture, and could they ask some friends what would happen if the Prime Minister did that specific thing, and then report back to us?

We spent most of a week working on our project to undermine Mozambique. Then we got the news. David and Shiri were suing the company for unfair dismissal and racial discrimination. Brad and Blake and I were white. Shiri was an Indian woman, and David was Jewish. The case should have been laughed out of court – who ever heard of an anti-Semitic Silicon Valley startup? – except that all the documentation showed there was no reason to fire David and Shiri. Their work looked good on paper. They’d always gotten good performance reviews. The company was doing fine – it had even placed ads for more programmers a few weeks before.

David and Shiri knew why they’d been fired. But it didn’t matter to them. They were so blinded with hatred for our company, so caught in the grip of the Scissor statement, that they would tell any lie necessary to destroy it. We were caught in a bind. We couldn’t admit the existence of Shiri’s Scissor, because we were trying to sell it to the Pentagon as a secret weapon, and also, publicly admitting to trying to destroy Mozambique would have been bad PR. But the court was demanding records about what our company had been doing just before and just after the dismissal. A real defense contractor could probably have gotten the Pentagon to write a letter saying our research was classified. But the Pentagon still didn’t believe us. The Colonel was humoring us, nothing more. We were stuck.

I don’t know how we would have dealt with the legal problems, because what actually happened was Brad went to David’s house and tried to beat him up. You’re going to think this was crazy, but you have to understand that David had always been annoying to work with, and that during the argument in Brad’s office he had crossed so many lines that, if ever there was a person who deserved physical violence, it was him. Suing the company was just the last straw. I’m not going to judge Brad’s actions after he’d spent months cleaning up after David’s messes, paying him good money, and then David betrayed him at the end. But anyhow, that was it for our company. Brad got arrested. There was nobody else to pay the bills and keep the lights on. Blake and I were coders and had no idea how to run the business side of things. We handed in our resignations – not literally, Brad was in jail – and that was the end of Name Withheld Online Ad Company, Inc.

We got off easy. That’s the takeaway I want to give here. We were unreasonably overwhelmingly lucky. If Shiri and I had started out by arguing about one of the US statements, we could have destroyed the country. If a giant like Google had developed Shiri’s Scissor, it would have destroyed Google. If the Scissor statement we generated hadn’t just been about a very specific piece of advertising software – if it had been about the tech industry in general, or business in general – we could have destroyed the economy.

As it was, we just destroyed our company and maybe a few of our closest competitors. If you look up internal publications from the online advertising industry around fall 2017, you will find some really weird stuff. That story about the online ads CEO getting arrested for murder, child abuse, attacking a cop, and three or four other things, and then later it was all found to be false accusations related to some ill-explained mental disorder – that’s the tip of the iceberg. I don’t have a good explanation for exactly how the Scissor statement spread or why it didn’t spread further, but I bet if I looked into it too much, black helicopters would start hovering over my house. And that’s all I’m going to say about that.

As for me, I quit the whole industry. I picked up a job in a more established company using ML for voice recognition, and tried not to think about it too much. I still got angry whenever I thought about the software design issue the Scissor had brought up. Once I saw someone who looked like Shiri at a cafe and I went over intending to give her a piece of my mind. It wasn’t her, so I didn’t end up in jail with Brad. I checked the news from Mozambique every so often, and it was quiet for a few months, and then it wasn’t. I still don’t know if we had anything to do with that. Africa just has a lot of conflicts, and if you wait long enough, maybe something will happen. The colonel never tried to get in touch with me. I don’t think he ever took us seriously. Maybe he didn’t even check the news from Mozambique. Maybe he saw it and figured it was a coincidence. Maybe he tried calling our company, got a message saying the phone was out of service, and didn’t think it was worth pursuing. But as time went on and the conflict there didn’t get any worse, I hoped the Shiri’s Scissor part of my life was drawing to a close.

Then came the Kavanaugh hearings. Something about them gave me a sense of deja vu. The week of his testimony, I figured it out.

Shiri had told me that when she ran the Scissor on the site in general, she’d just gotten some appropriate controversial US politics scenarios. She had shown me two or three of them as examples. One of them had been very specifically about this situation. A Republican Supreme Court nominee accused of committing sexual assault as a teenager.

This made me freak out. Had somebody gotten hold of the Scissor and started using it on the US? Had that Pentagon colonel been paying more attention than he let on? But why would the Pentagon be trying to divide America? Had some enemy stolen it? I get the New York Times, obviously Putin was my first thought here. But how would Putin get Shiri’s Scissor? Was I remembering wrong? I couldn’t get it out of my head. I hadn’t kept the list Shiri had given me, but I had enough of the Scissor codebase to rebuild the program over a few sleepless nights. Then I bought a big blob of compute from Amazon Web Services and threw it at the Reddit comment archive. It took three days and a five-digit sum of money, but I rebuilt the list Shiri must have had. Kavanaugh was in there, just as I remembered.

But so was Colin Kaepernick.

You’ve heard of him. He was the football player who refused to stand for the national anthem. If I already knew the Scissor predicted one controversy, why was I so shocked to learn it predicted another? Because Kaepernick started kneeling in 2016. We didn’t build the Scissor until 2017. Putin hadn’t gotten it from us. Someone had beaten us to it.

Of the Scissor’s predicted top hundred most controversial statements, Kavanaugh was #58 and Kaepernick was #42. #86 was the Ground Zero Mosque. #89 was that baker who wouldn’t make a cake for a gay wedding. The match isn’t perfect, but #99 vaguely looked like the Elian Gonzalez case from 2000. That’s five out of a hundred. Is that what would happen by chance? It’s a big country, and lots of things happen here, and if a Scissor statement came up in the normal course of events it would get magnified to the national stage. But some of these were too specific. If it was coincidence, I would expect many more near matches than perfect matches. I found only two. The pattern of Scissor statements looked more like someone had arranged them to be perfect fits.

The earliest perfect fit was the Ground Zero Mosque in 2009. Could Putin have had a Scissor-like program in 2009? I say no way. This will sound weird to you if you’re not in the industry. Why couldn’t a national government have been eight years ahead of an online advertising company? All I can say is: machine learning moves faster than that. Russia couldn’t hide a machine learning program that put it eight years ahead of the US. Even the Pentagon couldn’t hide a program that put it eight years ahead of industry. The NSA is thirty years ahead of industry in cryptography and everyone knows it.

But then who was generating Scissor statements in 2009? I have no idea. And you know what? I can’t bring myself to care.

If you just read a Scissor statement off a list, it’s harmless. It just seems like a trivially true or trivially false thing. It doesn’t activate until you start discussing it with somebody. At first you just think they’re an imbecile. Then they call you an imbecile, and you want to defend yourself. Crescit eundo. You notice all the little ways they’re lying to you and themselves and their audience every time they open their mouth to defend their imbecilic opinion. Then you notice how all the lies are connected, that in order to keep getting the little things like the Scissor statement wrong, they have to drag in everything else. Eventually even that doesn’t work, they’ve just got to make everybody hate you so that nobody will even listen to your argument no matter how obviously true it is. Finally, they don’t care about the Scissor statement anymore. They’ve just dug themselves so deep basing their whole existence around hating you and wanting you to fail that they can’t walk it back. You’ve got to prove them wrong, not because you care about the Scissor statement either, but because otherwise they’ll do anything to poison people against you, make it impossible for them to even understand the argument for why you deserve to exist. You know this is true. Your mind becomes a constant loop of arguments you can use to defend yourself, and rehearsals of arguments for why their attacks are cruel and unfair, and the one burning question: how can you thwart them? How can you can convince people not to listen to them, before they find those people and exploit their biases and turn them against you? How can you combat the superficial arguments they’re deploying, before otherwise good people get convinced, so convinced their mind will be made up and they can never be unconvinced again? How can you keep yourself safe?

Shiri read two or three sample Scissor statements to me. She didn’t say if she agreed with them or not. I didn’t tell her if I agreed with them or not. They were harmless.

I don’t hear voices in a crazy way. But sometimes I talk to myself. Sometimes I do both halves of the conversation. Sometimes I imagine one of them is a different person. I had a tough breakup a year ago. Sometimes the other voice in my head is my ex-girlfriend’s voice. I know how she thinks and I always know what she would say about everything. So sometimes I hold conversations with her, even though she isn’t there, and we’ve barely talked since the breakup. I don’t know if this is weird. If it is, I’m weird.

And that was enough. For some reason, it was the third-highest-ranked Scissor statement that did it. None of the others, just that one. The totally hypothetical conversation with the version of my ex-girlfriend in my head about the third Scissor statement got me. Shiri’s Scissor was never really about other people anyway. Other people are just the trigger – and I use that word deliberately, in the trigger warning sense. Once you’re triggered, you never need to talk to anyone else again. Just the knowledge that those people are out there is enough.

I thought I’d be done with this story in a night. Instead it’s taken me two weeks, all the way up until Halloween – perfect night for a ghost story, right? I’ve been alternately drinking and smoking weed, trying to calm myself down enough to think about anything other than the third Scissor statement. No, that’s not right, definitely trying not to think about either of the first two Scissor statements, because if I think about them, I might start thinking about how some people disagree with them, and then I’m gone. Three times I’ve started to call my ex-girlfriend to ask her where she is, and if I ever go through with it and she answers me, I don’t know what I will do to her. But it isn’t just her. Fifty percent of the population disagrees with me on the third-highest-ranked Scissor statement. I don’t know who they are. I haven’t really appreciated that fact. Not really. I can’t imagine it being anyone I know. They’re too decent. But I can’t be sure it isn’t. So I drink.

I know I should be talking about how we all need to unite against whatever shadowy manipulators keep throwing Scissor statements at us. I want to talk about how we need to cultivate radical compassion and charity as the only defense against such abominations. I want to give an Obamaesque speech about how the ties that bring us together are stronger than the forces tearing us apart. But I can’t.

Remember what we did to Mozambique? How out of some vestigial sense of ethics, we released a low-potency Scissor statement? Arranged to give them a bad time without destroying the whole country all at once? That’s what our shadowy manipulators are doing to us. Low-potency statements. Enough to get us enraged. Not enough to start Armageddon.

But I read the whole list. And then, like an idiot, I thought about it. I thought about the third-highest-ranked Scissor statement in enough detail to let it trigger. To even begin to question whether it might be true is so sick, so perverse, so hateful and disgusting, that Idi Amin would flush with shame to even contemplate it. And if the Scissor’s right then half of you would be gung ho in support.

You guys, who haven’t heard a really bad Scissor statement yet and don’t know what it’s like – it’s easy for you to say “don’t let it manipulate you” or “we need a hard and fast policy of not letting ourselves fight over Scissor statements”. But how do you know you’re not in the wrong? How do you know there’s not an issue out there where, if you knew it, you would agree it would be better to just nuke the world and let us start over again from the sewer mutants, rather than let the sort of people who would support it continue to pollute the world with their presence? How do you know that you’re not like the schoolkid who superciliously says “Nothing is bad enough to deserve a swear word” when the worst that’s ever happened to her is dropping her lollipop in the dirt. If that schoolkid gets kidnapped and tortured, does she change her mind? If she can’t describe the torture to her schoolmates, but just says “a really bad thing happened to me”, and they still insist nothing could be bad enough to justify using swear words, who do you side with? Then why are you still thinking I’m “damaged” when I tell you I’ve seen the Scissor statement, and charity and compassion and unity can fuck off and die? Some last remnant of outside-view morality keeps me from writing the whole list here and letting you all exterminate yourselves. Some remnant of how I would have thought about these things a month ago holds me back. So listen:

Delete Facebook. Delete Twitter. Throw away your cell phone. Unsubscribe from the newspaper. Tell your friends and relatives not to discuss politics or society. If they slip up, break off all contact.

Then, buy canned food. Stockpile water. Learn to shoot a gun. If you can afford a bunker, get a bunker.

Because one day, whoever keeps feeding us Scissor statements is going to release one of the bad ones.

When I was a sysadmin at the University of Pennsylvania, one of the grad students asked me if I knew that “gullible” was missing from the dictionary. This is the oldest trick in the book.

“Huh, really?” I said, and turned to my open terminal session. “Lemme see…”

% grep gullible /usr/dict/words || echo missing

missing

“…How about that! It's true!”

He was very surprised, and somewhat annoyed that his trick hadn't worked.

Wouldn't you expect that gullible would be in the word list used by

the Unix spell checker? Usually it is, but I was the sysadmin of

that machine, and I had removed it a couple of years before, just in

case.

Here's a list of the words from Webster's Second International Dictionary where the letters in the first half of the word are the same as the letters in the second half:

beriberi

ensconces

hotshots

intestine

intestines

reappear

restaurateurs

signings

teammate

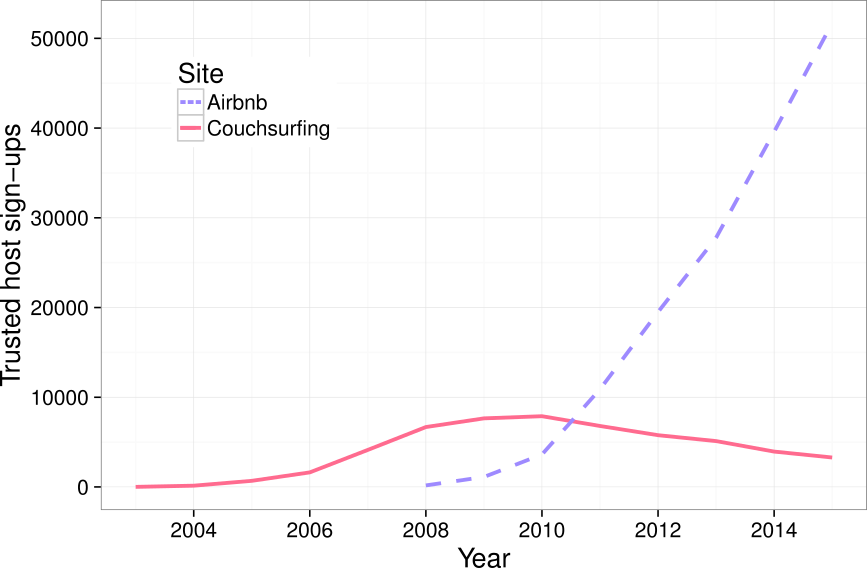

Couchsurfing and Airbnb are websites that connect people with an extra guest room or couch with random strangers on the Internet who are looking for a place to stay. Although Couchsurfing predates Airbnb by about five years, the two sites are designed to help people do the same basic thing and they work in extremely similar ways. They differ, however, in one crucial respect. On Couchsurfing, the exchange of money in return for hosting is explicitly banned. In other words, couchsurfing only supports the social exchange of hospitality. On Airbnb, users must use money: the website is a market on which people can buy and sell hospitality.

The figure above compares the number of people with at least some trust or verification on both Couchsurfing and Airbnb based on when each user signed up. The picture, as I have argued elsewhere, reflects a broader pattern that has occurred on the web over the last 15 years. Increasingly, social-based systems of production and exchange, many like Couchsurfing created during the first decade of the Internet boom, are being supplanted and eclipsed by similar market-based players like Airbnb.

In a paper led by Max Klein that was recently published and will be presented at the ACM Conference on Computer-supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing (CSCW) which will be held in Jersey City in early November 2018, we sought to provide a window into what this change means and what might be at stake. At the core of our research were a set of interviews we conducted with “dual-users” (i.e. users experienced on both Couchsurfing and Airbnb). Analyses of these interviews pointed to three major differences, which we explored quantitatively from public data on the two sites.

First, we found that users felt that hosting on Airbnb appears to require higher quality services than Couchsurfing. For example, we found that people who at some point only hosted on Couchsurfing often said that they did not host on Airbnb because they felt that their homes weren’t of sufficient quality. One participant explained that:

“I always wanted to host on Airbnb but I didn’t actually have a bedroom that I felt would be sufficient for guests who are paying for it.”

An another interviewee said:

“If I were to be paying for it, I’d expect a nice stay. This is why I never Airbnb-hosted before, because recently I couldn’t enable that [kind of hosting].”

We conducted a quantitative analysis of rates of Airbnb and Couchsurfing in different cities in the United States and found that median home prices are positively related to number of per capita Airbnb hosts and a negatively related to the number of Couchsurfing hosts. Our exploratory models predicted that for each $100,000 increase in median house price in a city, there will be about 43.4 more Airbnb hosts per 100,000 citizens, and 3.8 fewer hosts on Couchsurfing.

A second major theme we identified was that, while Couchsurfing emphasizes people, Airbnb places more emphasis on places. One of our participants explained:

“People who go on Airbnb, they are looking for a specific goal, a specific service, expecting the place is going to be clean […] the water isn’t leaking from the sink. I know people who do Couchsurfing even though they could definitely afford to use Airbnb every time they travel, because they want that human experience.”

In a follow-up quantitative analysis we conducted of the profile text from hosts on the two websites with a commonly-used system for text analysis called LIWC, we found that, compared to Couchsurfing, a lower proportion of words in Airbnb profiles were classified as being about people while a larger proportion of words were classified as being about places.

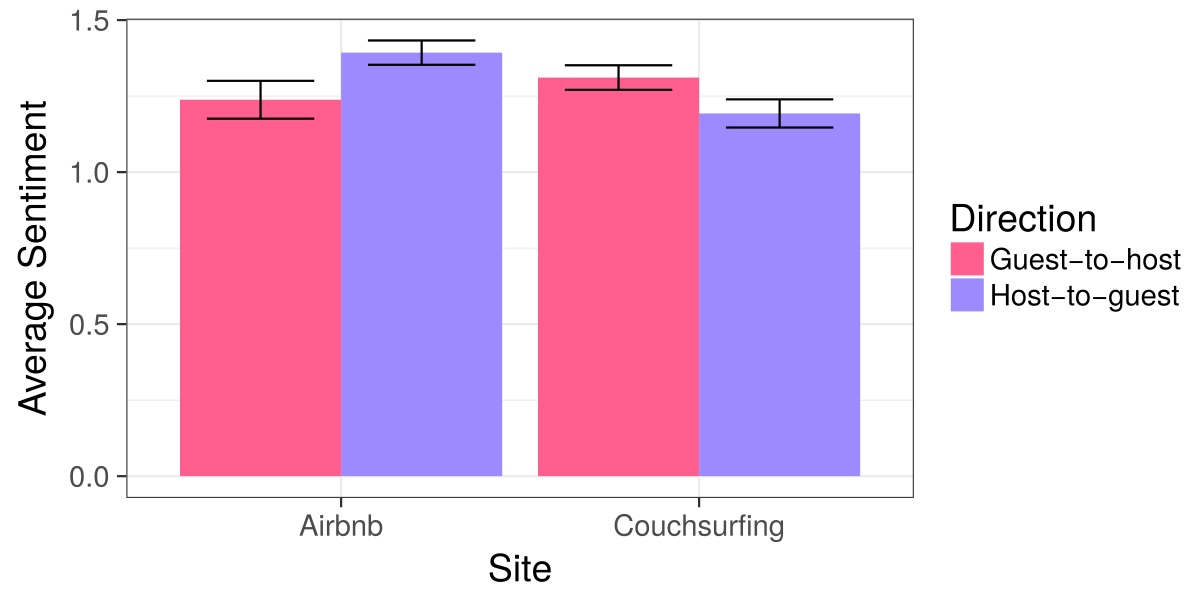

Finally, our research suggested that although hosts are the powerful parties in exchange on Couchsurfing, social power shifts from hosts to guests on Airbnb. Reflecting a much broader theme in our interviews, one of our participants expressed this concisely, saying:

“On Airbnb the host is trying to attract the guest, whereas on Couchsurfing, it works the other way round. It’s the guest that has to make an effort for the host to accept them.”

Previous research on Airbnb has shown that guests tend to give their hosts lower ratings than vice versa. Sociologists have suggested that this asymmetry in ratings will tend to reflect the direction of underlying social power balances.

We both replicated this finding from previous work and found that, as suggested in our interviews, the relationship is reversed on Couchsurfing. As shown in the figure above, we found Airbnb guests will typically give a less positive review to their host than vice-versa while in Couchsurfing guests will typically a more positive review to the host.

As Internet-based hospitality shifts from social systems to the market, we hope that our paper can point to some of what is changing and some of what is lost. For example, our first result suggests that less wealthy participants may be cut out by market-based platforms. Our second theme suggests a shift toward less human-focused modes of interaction brought on by increased “marketization.” We see the third theme as providing somewhat of a silver-lining in that shifting power toward guests was seen by some of our participants as a positive change in terms of safety and trust in that guests. Travelers in unfamiliar places often are often vulnerable and shifting power toward guests can be helpful.

Although our study is only of Couchsurfing and Airbnb, we believe that the shift away from social exchange and toward markets has broad implications across the sharing economy. We end our paper by speculating a little about the generalizability of our results. I have recently spoken at much more length about the underlying dynamics driving the shift we describe in my recent LibrePlanet keynote address.

More details are available in our paper which we have made available as a preprint on our website. The final version is behind a paywall in the ACM digital library.